La Pratica Della Mercatura

(Die Gepflogenheiten des Handels)

Francesco Balducci Pegolotti

2

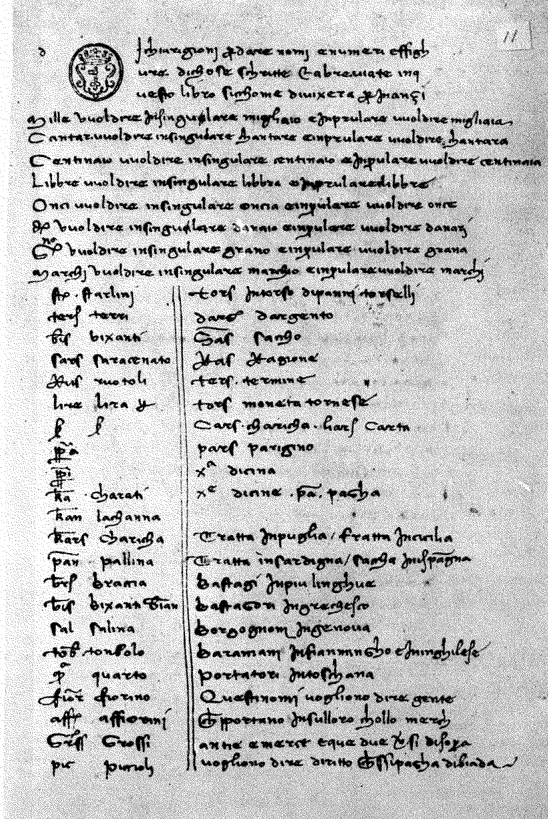

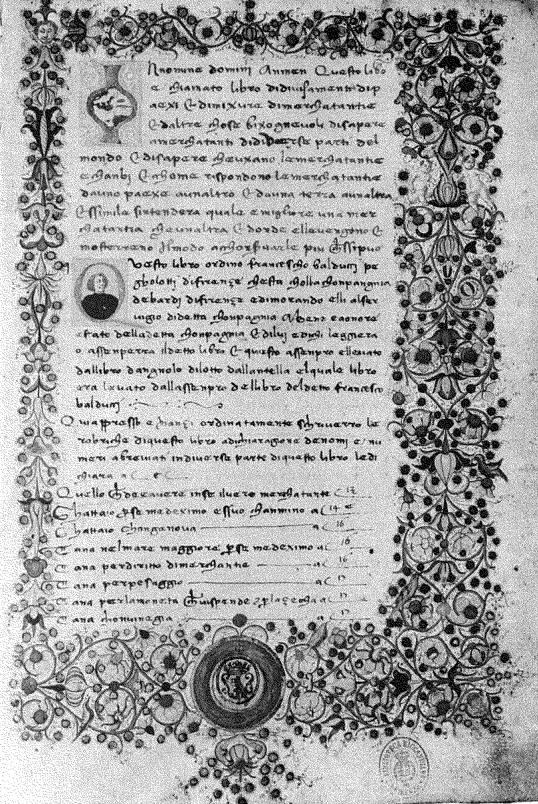

Plate I Codice Riccardiano 2441, fol. 1r.

Abbildung aus wikipedia übernommen.

Abbildung aus wikipedia übernommen.

3

In Nomine Domini, Ammen

iii

Dieses Buch heißt

LIBRO DI DIVISAMENTI DI PAESI E DI MISURE DI MERCATANTIE

(Buch über die

Einteilung

der Länder und die Maße des Handels)

und andere notwendige Dinge, die man über Waren

aus verschiedenen Teilen der Welt wissen sollte;

und was man über die Gebräuche bei Waren und

Wechseln wissen sollte, und wie sich die

Waren zwischen den Staaten (paese) bzw.

Ländern (terra) zueinander verhalten;

auf diese Weise wird man verstehen,

welche Ware besser ist als eine

andere und woher sie kommen

und sie zeigen die Möglichkeit,

sie länger aufzubewahren,

als man es vermag

aus verschiedenen Teilen der Welt wissen sollte;

und was man über die Gebräuche bei Waren und

Wechseln wissen sollte, und wie sich die

Waren zwischen den Staaten (paese) bzw.

Ländern (terra) zueinander verhalten;

auf diese Weise wird man verstehen,

welche Ware besser ist als eine

andere und woher sie kommen

und sie zeigen die Möglichkeit,

sie länger aufzubewahren,

als man es vermag

Dieses Buch hat Francesco Balducci Pegolotti aus Florenz

angeordnet. Pegolotti ist bei der Gesellschaft Bardi aus Florenz

(angestellt) und er steht im Dienst der besagten Gesellschaft

nicht nur zu ihrem Wohl, ihrer Ehre und ihrem Status, sondern auch für

denjenigen, der dieses Buch liest und als Beispiel nimmt.

Als Vorbild (assempro) hat das Buch von Agnolo di Lotto

aus Antella gedient, wobei sich dieses Buch Francesco Balduccis Buch zum

Beispiel (assempro) genommen hat.

4

Inhaltsverzeichnis

vi

Im Folgenden werden die Überschriften des Buchs ordentlich niedergeschrieben1

Das Inhaltsverzeichnis, wie es an dieser Stelle bei Evans (1936)

zu finden ist, darf hier in der HTML-Fassung ausgelassen werden. Die

Grobgliederung und die Teilgliederungen

in den jeweiligen Abschnitten gewährleisten einen schnelleren Zugriff und

würden hier nur wiederholt.

14

Erklärungen

- Namen, Zahlen und Abbildungen für Dinge, die in diesem Buch verwendet und abgekürzt werden

- Was den wahren und richtigen Kaufmann ausmacht

xix

Namen, Zahlen und Abbildungen für Dinge, die in diesem Buch verwendet und abgekürzt werden

Hundert wird im Singular centinaio und im

Plural centinaia genannt.

Last: Cantar

heißt im Singular cantare und im Plural

cantara.

Pfund nennt man im Singular

libbra und im Plural libbre.

Unze: Onci heißt im Singular

oncia und im Plural once.

Weizen, Getreide oder Korn4

nennt man im Singular grano und im Plural grana.

Mark heißt im Singular marchio und im

Plural marchi.

[[ In dieser Form ist die Tabelle inhaltsleer. ]]

| 5starlini | carica | intorso di Stoffe torselli |

| terrì6 | pallina | Silber |

| Bezant | braccia | sacca |

| sarazenisch | Bezant, bianchi | Grund |

| ruotoli | salina | Frist/Fälligkeit |

| lira | tombolo | Geld tornese |

| <soldi> | vierte | carica, Kontrakt/Dokument |

| . . . . . | Gulden | Pariser |

| <perperi> | nach Florin | Zehn |

| Karat | Grossi | dicine, bezahlen7 |

| die canna | Kleingeld |

15

Träger bzw. Tragegebühr: Die folgenden Namen werden für

Menschen verwendet, die Waren und Güter auf ihrem Nacken tragen.

Gleichzeitig werden die Namen auch für Gebühren verwendet, die man mit

Getreide bezahlt.

Tratta in Apulien und tratta8 in Sizilien.Tratta in Sardinien. Sacca in Spanien.Bastagi in mehreren Sprachen.Bastagori in Griechisch.Borgognoni in Genua.Baramani in Flämisch oder Englisch.Portatori in der Toskana.

Gebühren, Abgaben, Maut oder Zölle: Die folgenden Namen

bezeichnen Gebühren, die man auf Waren, Güter und andere Dinge zahlt,

die jemand anbietet, exportiert oder durchleitet namentlich für

abgeschlossen Orte, Länder oder Gebiete.

Tamunga in Täbris1 und für ganz Persien. xxTamunga2 in Trapezunt.Tamunga in Asow.Tamunga in Feodossija und für alle Länder der Tartaren3 undPesadone in Kleinarmenien.Doana in allen Länder der Sarazenen und in Sizilien.Doana in Neapel und für das ganze Königreich Apulien.Piazza, fondaco, bindanaio, ebenso für ganz Sizilien wie für das ganze Königreich Apulien.Comerchio für alle Länder der Griechen.Comerchio4 auf Zypern.Dazio in Venedig.Gabella für die ganze Toskana.Spedicamento und pedaggio in Genua.Chiaveria in der ganzen Provence.Lelda in einem Teil der Provence und in Frankreich.Malatolto, pedaggio und bara im ganzen Königreich Frankreich.Toloneo5 für ganz Flandern.Toloneo6 für ganz Brabant.Costuma auf der ganzen Insel von England.Fedo in Tunis (Barbarei).Munda in Friaul.Mangona und talaoch in Spanien.

‘Come viene della falda’ bedeutet als Ganzes,7

so wie die geschorene Wolle des Schafs kommt, d.h. das vollständige Vlies des

ganzen Schafs, von dem nichts abgeschnitten ist.

16

Brisciata1

heißt Auswahl, d.h., das Woll-Vlies ist mit mehr Vernunft gemacht.

Gute Wolle ist die beste Sorte, wenn sie briscia (s.o.) ist.

Wolle mittlerer Qualität (moiana2),

ist die mittlere Güte Wolle, wenn sie briscia (s.o.) ist.

Wolle minderer Qualität (locchi) ist die dritte Güte Wolle, wenn

sie briscia (s.o.) ist.

Verdreckte Wolle (steccata)3

bedeutet ein Woll-Vlies befreit von Dreckspritzern der Schafe, die an

der Wolle hängen.

Bündel (torce4)

bezeichnet ein gefaltetes oder aufgerolltes Woll-Vlies.

Bündel Wolle (pugnea)5

bedeutet ein Woll-Vlies, das dann brisciata (s.o.) ist. Man bereitet es zu

einer Rolle vor, woraus eine Art großer Ball gemacht wird.

xxi

Frachtkosten: Nolo in mehreren lateinischen

Sprachen, freto in Flämisch, Englisch und Spanisch.

Diese Namen bezeichen die Pfennige, die man den Schiffseigentümern bezahlt,

die die Waren über das Meer von einem zum anderen Land führen.

Lotse: Pedoto in mehreren Sprachen,

ludumano in Flämisch und Englisch. Diese Namen

werden für Menschen verwendet, die mit dem Meer, dem Land, den Küsten und

den Seehäfen vertraut sind, sowie für Menschen, die die Schiffe sowohl in

den Häfen als auch an Land lenken.

Hebegebühr: Sportellaggio in mehreren

Sprachen, ghindaggio in Flämisch und Englisch,

ghindaggio in Spanien. Diese Namen verwendet man

für „Weingeld”, das man den Seeleuten der Schiffe gibt, die beim Entladen

der Schiffsladung helfen.

Boote: Folgende Namen bezeichnen kleine Boote oder Schiffe, die die Waren

von einem Land zum anderen bringen.

Barca in mehreren Sprachen.Gondel in mehreren Sprachen.Copano7 in der Provence,17 Taferese auf Zypern,Feuto1 in Flandern.Battello und batto in Frankreich.Paliscarmo in mehreren Sprachen.

Lager(haus): Folgende Namen verwenden sie für Orte, an denen die

Waren bewacht wird, wo ansässige Kaufleute bleiben und Schutz suchen, um

Geld zu verdienen, und wo sie ihre Waren, Güter, Schriftstücke und dergleichen

Sachen sicher aufbewahren.2

Fondaco und bottega in der Toskana.Volta in Genua.Stazione in Französisch.Magazzino in mehreren Sprachen.Celliere in Flämisch.

Marktplatz: Folgende Namen verwendet man für Orte, wo Waren

– alle Arten Lebensmittel, Dinge des täglichen Bedarfs, Getreide

und Vieh – in der Stadt, Burg oder Ortschaft verkauft werden,

sowohl kontinuierlich als auch4

zu gewissen Zeiten (überlicherweise Wochen bzw. Monate des Jahres).

Mercato in der Toskana.Piazza in mehreren Sprachen.Bazarra und raba in Genua.Fondaco in mehreren Sprachen.Fonda3 auf Zypern.Alla (Markthalle) in Flandern. xxiiSugo in Sarazenisch.Fiera in der Toskana und in mehreren Sprachen.Panichiero in Griechisch.

Gold und Silber:

Barren (buglione) und Münzen

(bolzonaglia) bedeuten Gold und Silber in Platten,

Stangen, Bruchsilber oder Gold- bzw. Silbergeld, das nicht an diesen Orte

umläuft. Unter Barren versteht man zerbrochene Dinge, die

18

zerlegt und eingeschmolzen werden; die Münzen

sind dagegen so viel wert, wie nicht an diesen Orten kursierendes

Kleingeld, sie dienen dem Schmelzen und Zerlegen.

(Stoff)Ballen: Folgende Namen verwendet man für Stoffballen oder

Ballen andere Güter, die man zusammenknüpft, damit sie verbunden bleiben und

von einem Platz zum nächsten, von einem Land zum nächsten zu Land oder über

das Meer versendet werden können.

Ghibba1 in Flämisch.Torsello in mehreren Sprachen.Balla in mehreren Sprachen.Fardello in mehreren Sprachen.Pondo in mehreren Sprachen.Fardo in Syrisch.

Makler: Folgende Namen bezeichnen Personen, die man

zwischenschaltet, um Märkte für Waren oder andere Dinge zu schaffen,

die zwischen Händlern gekauft bzw. verkauft werden; gleiches gilt für den

Tausch und für jede andere Ware, die jemand verkaufen oder kaufen will.

Sensale in mehreren Sprachen.Curattiere in mehreren Sprachen.Mezzano in mehreren Sprachen.Messeto in Venedig.

xxiii

Stofflängen: Folgende Namen werden für Längenmaße verwendet, nach denen

man Wollstoffe, Leinen, Sendal-Seide

und andere Dinge, die nach Länge gehandelt werden, misst.

canna, braccio und passo in mehreren Sprachen.Alla auf Französisch Flämisch und Englisch,3 undCorda auf Provenzalisch.Picco auf Griechisch, Persisch und in mehreren Sprachen.Vara auf Spanisch.

Acra, atra4

benennt in Flandern und Brabant die Anzahl für Dinge, die nach

acra bzw. atra

verkauft werden: Man gibt davon zehn Stück je6

acra bzw. atra.

19

Wachen: Tantaullo1

in der Sprache der Tartaren, guardia in mehreren

Sprachen. Diese Namen bezeichnen Menschen, die die Orte und Wege für die

Herren und die Gemeinschaft bewachen.2

Nil-Boot: Giermo bedeutet auf Sarazenisch

„große Schiffe”, die die Waren von Damiette über den Fluss bis nach Kairo

(Bambillonia) und von Kairo über den Fluss bis zum Indischen Ozean bringen.

Dolmetscher: Turcimanno in mehreren

Sprachen oder calamanci in der Sprache der Tartaren

sind Personen, die vermitteln (temperano) und Sprachen, die man nicht

gleichzeitig versteht, von einer in eine andere übersetzen.

20

xxiv Was den wahren und richtigen Kaufmann ausmacht

Er sollte stets redlich sein,er sollte lange am Herkunftsort (provedenza) bleiben, [[Beständigkeit, evtl. auch ökonomische Weitsicht]]was er verspricht, darf nicht unvollständig sein; [[Vertrauenswürdigkeit]]er sollte, wenn es geht, von schöner und ehrlicher Enthaltsamheit sein [[gute Manieren und ehrliches Verhalten]]je nachdem, welche Fähigkeiten (mestieri) oder Gründe (ragione) gemeint sind.Wer sparsam (oder achtsam) kauft und großzügig verkauft,äußeren Tadel mit nettem Willkommen (entgegnet),1 [[Kundenfreundlichkeit]]die Kirche besucht und für Gott spendet,steigt im Wert (Ansehen) und verkauft nach einem Grundsatz.Untersage Wucher, das „Spiel von Zara”und ‘torre via al tutto’, [[kein Wucher oder Glücksspiel]]schreibe den richtigen Grund und irre nicht. [[korrekte Buchführung]]Amen2 21

1

Hinweis zur Reise nach Kathay (Nördliches China)

- Auf dem Weg von Asow losgehen und mit Ware zurückkommen

- Notwenige Kosten für Kaufleute, die besagte Reise nach Kathay unternehmen wollen

I

Auf dem Weg von Asow losgehen und mit Waren zurückkommen

Zunächst sind es von Asow (Mündung des Don) nach Astrachan (Mündung der

Wolga) 25 Tage mit dem Ochsenkarren, aber mit dem Pferdekarren nur 10–12

Tage. Auf dem Weg begegnet man vielen Mongolen, d.h. Bewaffneten. Von

Gittarcan nach Sarai (Hauptstadt der Mongolen an der Wolga) dauert es

einen Tag auf dem Fluss. Von Sarai nach Saraichuk dauert es 8 Tage über

einen Fluss; man kann über Land gehen oder über das Wasser fahren, wobei

sich über Wasser weniger Ausgaben für die Ware ergeben. Von Saraichuk bis

Urgench dauert es 20 Tage mit dem Kamelkarren; wer mit Waren geht, dem

wird empfohlen, nach Urgench zu gehen, weil es dort einen Handelsplatz mit

großen Absatzmöglichkeiten (spacciativa) gibt. Von Urgench nach Otrar

(heute Kasachstan) dauert es 35–40 Tage mit dem Kamelkarren. Wer

Saraichuk verlässt und direkt nach Otrar geht, benötigt 50 Tage; ohne Ware

wäre das besser, als über Urgench zu gehen. Von Otrar1

nach Armalec dauert es 45 Tage mit einem Packesel, dabei trifft man jeden

Tag weitere Mongolen. Von Armalec bis nach Kanchow (Ganchau)2

dauert es 70 Tage mit dem Esel und von Kanchow (Ganchau)2

bis man zu einem Strom namens [...] kommt, dauert es 45 Tage zu Pferd. Von dem

Strom kannst du3

nach Hangzhou gehen und dort die sommi4

Silber aus deinem Besitz verkaufen, weil es dort einen Handelsplatz mit

großen Absatzmöglichkeiten (spaccativa) gibt. Hangzhou verlässt man mit

dem Papiergeld, das man aus dem Verkauf des Silbers in Hangzhou zieht und

das sie balishi5 nennen.

2

Vier Teile dieses Geldes haben den Wert eines sommo

Silber auf dem Gebiete von Kathay (nördliches China). Von Hangzhou nach

Peking, welches die Hauptstadt des Landes Kathay ist, geht man in 30

Tagen.

II

Notwenige Kosten für Kaufleute, die besagte Reise nach Kathay unternehmen wollen

Zunächst sollte man sich einen langen Bart wachsen lassen und sich

nicht rasieren. In Asow sollte man sich einen Dolmetscher besorgen.

Dabei sollte man nicht danach trachten, mit einem schlechten (Dolmetscher)

gegenüber einem guten (Geld) zu sparen, denn der gute kostet nicht

übermäßig viel (il buono non costa quello d’ingordo che l’uomo non

– s’ene megliori via più). Zusätzlich zum Dolmetscher sollte man

nicht weniger als als zwei gute Diener einstellen, die die kumanesische

Sprache gut kennen. Wenn der Kaufmann von Asow irgendeine Frau mit sich

nehmen will, kann er das tun, aber es gibt keinen Zwang, wenn er keine

mitnehmen will.

22

Allerdings wird sein Zustand auch besser sein, wenn er eine mitführt als

wenn nicht und falls er eine mitnimmt, sollte sie die kumanesische Sprache

wie der Diener kennen. Von Asow bis Gittarcan sollte man sich mit

Lebensmitteln für 25 Tage versorgen, d.h. Mehl und Stockfisch, denn

Fleisch findet man auf dem Weg an allen Orten. Ebenso sollte man sich an

allen Orten, zu denen man auf besagter Reise von einem zum anderen Land an

den oben besagten Tagen kommt, mit Mehl und Stockfisch versorgen, denn

andere Dinge und insbesondere Fleisch findet man ausreichend.

Der Weg, den man von Asow nach Kathay (nördliches China) geht, ist

sowohl bei Tag als auch bei Nacht äußerst sicher, laut dem, was die

Kaufleute erzählen, die ihn benutzt haben. Es sei denn, der Händler stirbt

unterwegs. Dann gehören alle Sachen dem Landesherrn, auf dessen Gebiet der

Kaufmann gestorben ist, und die Beamten des Landesherrn würden alles nehmen.

Ähnliches gilt, wenn er in Kathay stirbt. Genau genommen, wenn er seinen

Bruder, einen engen Freund oder einen Kameraden, der sagt, sie seien

Brüder, dabei hätte, würde ihm der Besitz des Toten gegeben; auf diese

Weise würde man es schaffen, alles zu behalten. Dennoch besteht eine

weitere Gefahr, nämlich wenn der Landesherr stirbt und der designierte

Landesherr noch nicht ernannt ist. In dieser Zwischenzeit sind den Franken

– sie nennen alle Christen aus Romania und westlich davon Franken

– und anderen Fremden gegenüber manchmal Neuerungen eingeführt

worden.

3

Dann ist der Weg nicht sicher, bis der neue Landesherr, der nach dem

Verstorbenen regieren muss, ernannt worden ist.

Kathay (nördliches China) ist eine Provinz, wo es viele Regionen und

Siedlungen (casali) gibt. Darunter gibt es eine, nämlich die Hauptstadt

Peking, wo die Händler Schutz suchen und wo il forzo der

Waren gemacht wird. Die besagte Stadt hat einen Umkreis von einhundert

Meilen und sie ist voll von Menschen, Ortsansässige und Einwohnern aus

dieser Stadt.

Man sagt, dass ein Kaufmann mit einem Dolmetscher und zwei Dienern und

mit einem Besitz im Wert von 25 tausend

Florin bis Kathay Ausgaben von 60–80

sommi Silber hat, wenn man haushalten

(fare

masserizia) will. Für den ganzen Rückweg von Kathay nach Asow

rechnet man 5 oder etwas weniger sommi auf die

soma,

wenn man die Kosten für Lebensmittel (bocca = Mund), den Lohn für die Diener

und alle anderen Ausgaben zählt. Dabei kann der sommo

5 Florin wert sein.

Man sagt, dass ein Karren von nur einem Ochsen gezogen werden muss, wobei

der Karren 10 genuesischen cantara entspricht; der

Kamelkarren wird von drei Kamelen gezogen und der Karren entspricht hier

30 genuesischen cantara; schließlich wird der

Pferdekarren von einem Pferd gezogen, wobei der Karren üblicherweise

6½ genuesischen cantara Seide zu je

250 genuesischen Pfund entspricht. Ein Bündel

(scibetto) Seide rechnet man zu

110–115 genuesischen Pfund.

Man behauptet, dass der Weg von Asow nach Sarai weniger sicher sei als der

ganze restliche Weg; wenn aber dort, wo der Weg in schlechtester

Verfassung ist, 60 Männer dabei sind, fühlte man sich so sicher wie in

seinem Zuhause.

Jedermann, der von Genua oder Venedig zu dem besagten Ort gehen und die

23

Reise nach Kathay unternehmen möchte, würde Gewebe mitbringen,

und er würde gut daran tun, wenn er nach Urgench ginge; in Urgench würde

er sommi kaufen und mit ihnen weiterziehen, ohne

in andere Ware zu investieren. Es sei denn sie verlangen für sehr feines

Gewebe keine höheren Ausgaben als für gröberes Gewebe und man hätte nicht

bereits ein paar kleine Ballen sehr feines Gewebe.

Die Kaufleute können auf dem Weg entweder auf einem Pferd, einem Esel

oder irgendeinem Tier, das sie aufsteigen lässt, reiten.

Alles Silber, das Kaufleute bringen und das nach Kathay geht,

lässt der Herr von Kathay für sich einziehen und in seine Schatzkammer

legen. Den Kaufleuten, die es dorthin bringen, geben sie dafür Papiergeld,

das sind gelbe Dokumente, die mit dem Siegel des besagten Herrn gestempelt

sind. Dieses Geld nennt man

balisci3.

4

Mit diesem Geld kannst du Seide und jede andere Ware oder Sache, die du

erwerben möchtest, kaufen und du wirst sie finden (truovi). Jedermann im

Land ist verpflichtet, das Papiergeld anzunehmen und doch kauft man nicht

zuviel von der Ware, (nur) weil es Papiergeld ist. Von dem besagten

Geld gibt es drei Sorten, das eine ist mehr wert als das andere, je

nachdem wie sie durch den Herrn bei der Währung angeordnet sind.

Man sagt, dass in Kathay ein sommo Silber

19–20 Genueser Pfund Seide aus Kathay erbracht

hat. Dabei dürfe der sommo 8½

Genueser Unzen wiegen und eine Legierung von 11

Unzen und 17 Pfennig Feinsilber

je Pfund haben. Außerdem wird gesagt, dass man in

Kathay 3–3½ Stücke Camocas für

einen sommo und zwischen 3½ und 5 Stück

Nacchetti für einen

sommo Silber haben wird.

Eine Mena4 aus Sarai macht nach dem Gewicht von Genua 6 Pfund, 2 Unzen. IIIEine Mena aus Urgench macht in Genua 3 Pfund, 9 Unzen.Eine Mena aus Otrar macht in Genua 3 Pfund, 9 Unzen.Eine Mena aus Armaleco macht in Genua 2 Pfund, 8 Unzen.Ein Mena aus Kanchow (Ganchau)5 macht in Genua 2 Pfund.

Asow am Schwarzen Meer

- Eingangszoll, den man in Asow für Waren bezahlt; beim Verlassen braucht man nichts zu bezahlen

- Welche Wiegegebühr für Waren man in Asow bezahlt

- Wie das Gewicht und das Maß aus Asow in diversen Teilen der Welt umgerechnet werden; zunächst mit Venedig

- mit Neapel

- Geld:

- Aspro = 16 folleri

- Gewicht:

-

Cantaro (wie Genua)

1 schweres Pfund = 20 genuesische ruotoli = 12 tocchetti

1 leichtes Pfund = 1 genuesisches Pfund

1 sommo = 45 saggi - Raummaß:

- cascito, Fass mena, metri

- Länge:

- picco

In Asow gibt es mehrere Arten Gewichte und Maße, die sich wie folgt gliedern:

Cantaro, welche ist das genuesische cantaro.Schweres Pfund, welches ist 20 genuesische ruotoli6.Ruotolo.1 schweres Pfund = 20 ruotoli 24leichtes Pfund, welches ist das genuesische Pfund.Tocchetto.1 schweres Pfund = 12 tocchettiSaggi (1 sommo = 45 saggi).Picco.

Wachs, Ladanum, Eisen, Zinn, Kupfer,

Pfeffer, Ingwer, alle grobe Spezereien,

Baumwolle, Krapp, Talg, Käse, Flachs, Olivenöl, Honig, und dergleichen

werden nach schweren Pfund verkauft .

Seide, Safran, Amber bearbeitet nach Art di

paternostri (unseres Vaters) und alle feinsten Spezereien werden nach

leichten Pfund verkauft.

Feh zu Tausend, 5 und 1020 desselben je

einen Tausend.

Hermelin zu Tausend, und 1000 desselben1

je einen Tausend.

Füchse, Zobel, Wiesel, Marder, Luchsfell und alles Tuch aus

Seide oder Gold werden stückweise verkauft.

Tuch und canovacci von

jeder Art werden nach picco verkauft.

Störe werden im Bündel zu 20 Stück verkauft.

Rindsleder zu hundert an der Zahl, und 100 derselben je Hundert.

Pferde- und Ponyleder wird stückweise verkauft.

Gold und Perlen werden nach saggio verkauft.

Weizen, jedes andere Getreide und Hülsenfrüchte werden in Asow

nach einem Maß, das sie cascito nennen, verkauft.

Griechischer Wein und alle lateinischen Weine werden im Fass, so wie es

ist, verkauft.

Weine aus Monemvasia, Tirilye und Candia werden hier

nach metri verkauft.

Kaviar wird nach fusco verkauft, dabei besteht

jeder fusco aus einer halben Fischhaut und die ist

von der Mitte abwärts bis zum Schwanz voller Fischrogen.

IV Eingangszoll, den man in Asow für Waren bezahlt; beim Verlassen braucht man nicht zu bezahlen

Gold, Silber und Perlen bezahlen in Asow keinen Zoll,

keine Tamunga und keine andere Gebühr.

Wein, Rindsleder, Stör und Ponyleder: Diese Dinge kosten Genuesen und

Venezianer 4 Prozent, alle anderen bezahlen 5 Prozent.

25

Welche Wiegegebühr für Waren man in Asow bezahlt 1

Seide, von jedem Pfund 15 Aspre.

Alle anderen Dinge, von je 3 cantara [...] Aspre

Alle anderen Dinge, von je 3 cantara [...] Aspre

In Asow verwendet man sommi:

1 sommo = 45 saggi in Asow

Die Aspre Silber halten eine Legierung von 11

Unzen und 17 Pfennig

Feinsilber je Pfund. Wer Silber in der Münze von Asow

einzahlt, lässt sich von der Münze aus einem der genannten

sommi 202 Aspre a conto schlagen;

und obwohl die Münze von dem sommo

202 Aspre machen soll, gibt sie davon nicht mehr als

190 Aspre zurück,

6

den Rest behält sie für die Bearbeitung und als Gewinn der Münzen

(Schlagschatz) ein, sodass 190 Aspre den Wert eines

sommo aus Asow haben. Die

sommi (darunter sind Stangen Silber der obengenannten

Legierung) gibt man als Gewicht in Zahlung. Allerdings wiegen die Stangen

nicht alle gleich viel, so dass man für den Restbetrag (bilancia) bis zum

erforderlichen sommi Silberstangen oder eine Menge

peso (Gewicht) einzahlt. Bei weniger als dem Gewicht

eines sommo bezahlt man Aspre.

Jeder sommo sollte 45 saggi

nach dem Gewicht von Asow sein.Man verwendet in Asow ein Geld, das gänzlich aus Kupfer und ohne

Silber ist und das folleri genannt wird.

1 Aspro = 16 folleri

Die besagten folleri verwendet man nicht bei der

Zahlung von Waren, sondern nur bei Kräutern und kleinen, notwendigen Dingen

auf dem Land.V Wie das Gewicht und das Maß aus Asow in diversen Teilen der Welt umgerechnet werden; zunächst mit Venedig

1 Cascito Getreide nach dem Maß von Asow macht

in Venedig 5 staia.

1 schweres Pfund aus Asow macht

in Venedig 30 leichte Pfund.

1 Tocchetto aus Asow macht in Venedig

2 Pfund und 7 Unzen nach

leichtem Gewicht.

mit Neapel

1 Fass mena griechischer Wein aus Neapel macht

in Asow 50 metri.

Feodossija

- Abgaben auf Waren, die man in Feodossija kauft

- Wie die Maße und Gewichte aus Feodossija in diversen Länder umgerechnet werden; zuerst mit Pera

- mit Venedig

- Geld:

- Gewicht:

-

1 cantaro = 7 schwere

Pfund = 150 genuesische Pfund

1 schweres Pfund = 14 2/7 ruotoli

1 leichtes Pfund = 1 genuesisches Pfund

saggio

- Raummaß:

- Scheffel (moggio)

- Länge:

- picchio

In Feodossija gibt es mehrere Arten Gewichte und Maße, die wie folgt

eingeteilt sind:

Cantare, das mit dem genuesischen cantare übereinstimmt. 7Schwere Pfund: 7 Pfund machen 1 cantare in Genua. 26Ruotoli: 14 2/7 davon machen 1 schweres Pfund.Leichtes Pfund, das dem genuesischen Pfund entspricht.Saggio, welches mit dem saggio aus Pera übereinstimmt.Picchio.

Abgaben, die man auf Waren in Feodossija bezahlt

Alle Personen außer den Genuesen bezahlen 3 Prozent für die Entnahme

(wohl Export) und das Betreten.

Genuesen bezahlen 3½ Prozent; ein halbes Prozent geht an die

Gemeinschaft der Genuesen selbst und 3 Prozent sind für den Herren von Feodossija.

Wie die Maße und Gewichte aus Feodossija in diversen Länder umgerechnet werden (zuerst mit Pera)

2 Moggia Getreidefutter nach dem Maß von Feodossija ergeben in

Pera 2 1/5, wenn man es in Feodossija von den Genuesen erhält,

und 2¼, wenn man es von den Tataren empfängt.

mit Venedig

1 Scheffel nach dem Maß aus Feodossija macht in

Venedig 4⅓ staia3.

Täbris in Persien

- Täbris per se das gleiche, nach dem Gewicht und dem Maß werden hier die Waren verkauft

- Abgaben auf Waren, die man in Täbris kauft

- Ordentliche Aufstellung der Kosten für den Transport von Waren über Land von Ajas (Kleinarmenien) nach Täbris

- Wie die Gewichte und Maße aus Täbris in diversen Ländern umgerechnet werden (zunächst mit Trapezunt)

- mit Pera und Konstantinopel

- mit Ajas in Kleinarmenien

- mit Famagusta (Zypern)

- mit Venedig

- mit Genua

- Geld:

-

1 casinino Gold = 1 saggio Gold

= 28–29 Aspre

Aspre torrisini (aus Täbris) bzw. grossi Kleingeld

Bezant torrisino = 2 grossi = 6 Aspre - Gewicht:

-

Pfund torrisino

1 sommo = 45 saggi

mena, peso

Gold: saggi

Silber: Karat

aspers - Raummaß:

- Länge:

- picchio

Täbris per se das gleiche, nach dem Gewicht und dem Maß werden hier die Waren verkauft

Alle groben Spezereien werden in Täbris nach Hundert

mene verkauft und nach

dem Wert von soundso vielen Bezant

torrisini

der Hundert mene.

Feine Spezereien werden in Täbris nach Zehn

mene verkauft.

Seide nach großer mena, Leinen

nach picchio.

Indigo nach peso

(Gewicht)4 mit der ganzen Verpackung und dem Leder.

Koralle, Amber conce nach Art

paternostri (unseres Vaters), Quecksilber und Zinnober

werden nach Zehn mene grobe

Spezereien verkauft.

Zinn nach Hundert mene grobe Spezereien.

Kamelott nach Stück und Vorhänge aus Wolle stückweise.

8

Perlen nach Zehn saggi,

d.h. Perlen von 2½ bis zu 14 Karat, d.h. a conto je Draht zu 36

Perlen; ab 14 Karat werden Perlen nach

saggio verkauft.

27

Feh nach Tausend di conto.

Fehrücken nach Hundert.

Hermelin zu 40 Stück.

Leopardenfell, Marder und Wiesel verkauft man in Täbris als

Ganzes.

Gold und Silber werden gehandelt, und zwar Gold nach saggi

und Silber nach Karat Gewicht.

Alle groben und feinen Spezereien, die einer Gebühr unterliegen, prüft

man in Täbris, die Steuer trägt der Verkäufer nur nicht bei Schellack:

Die Steuer für Schellack geht zur einen Hälfte an

den Verkäufer und zur anderen an den Käufer.

In Täbris wird Gold- und Silbergeld verwendet.

Das Goldgeld wird casinini Gold genannt, seine Legierung ist 23 1/8 Karat Feingold je Unze; damit zahlt man nach dem Gewicht des saggio, denn jeder saggio Goldgewicht ausgemünzt nach der Prägung der Münze des Herrn ist ein casinino Gold bei Zahlungen.

Das Goldgeld wird casinini Gold genannt, seine Legierung ist 23 1/8 Karat Feingold je Unze; damit zahlt man nach dem Gewicht des saggio, denn jeder saggio Goldgewicht ausgemünzt nach der Prägung der Münze des Herrn ist ein casinino Gold bei Zahlungen.

1 casinino Gold = 28–29 Aspre

torrisini Silber

Das Silbergeld hält eine Legierung von

11 Unzen 17 Pfennig Feinsilber

je Pfund. Die Münze des Herrn schlägt zwei Arten

grossi Silber:

-

Grossi, die

zu 635

Grossi a conto je Pfund

torrisini ausgebracht werden,

1 Bezant torrisino = 2 Grossibei der Zahlung von Waren;

- und das andere Geld ist grossi Kleingeld, das zu

190 a conto je Pfund

torrisini ausgebracht wird;

diese grossi Kleingeld werden

Aspre genannt.

1 Bezant torrisino = 6 Aspre torrisini

(1 Grossi = 3 Aspre)

Gebühren, die man auf Waren in Täbris bezahlt

Für das, was man nach dem Gewicht von Täbris kauft oder verkauft, bezahlt

man 5 Bezant weniger ½ Aspre

camunoca pro hundert.

9

Drapperie aus Wolle, Leinen, Pelzwaren, Kamelott, Zinn und alles, was

im Kleinen und nach dem Maß verkauft wird, bezahlt man eine

camunoca von

4 [[Bezant?]] weniger ⅓ Prozent.

28

Dem Makler bezahlt man ½ Prozent oder mehr aus Gefälligkeit.

Silber und Perlen sind frei, für sie bezahlt man keine

tamenga, weder beim Betreten noch

beim Verlassen.

VI Ordentliche Aufstellung der Kosten für den Transport von Ware über Land von Ajas (Kleinarmenien) nach Täbris

Dies ist je soma zu verstehen und wenn es nicht genau

ein soma wäre, würde man im Verhältnis (all'avenante)

mehr oder weniger bezahlen. Die Kosten lassen sich wie folgt gliedern:

Zuerst von Ajas bis Colidara, d.h. für alle Länder des Königs von

Kleinarmenien, in Summe 41 taccolini und

3½ Pfennig je soma für ein

Kamel oder ein anderes Tiere.

1 taccolino = 10 Pfennig

Diese taccolini haben den Wert 41

Aspre torrisina

je soma, damit lässt sich der taccolino

zu etwa einem Aspre bewerten.

1 Bezant = 6 Aspre in Täbris (Torisi)

In Gandon, d.h. beim Betreten der Länder des Bonsaet, also des Herrn der

Tartaren, für die Gebühr je soma 20 Aspre.

In diesem Ort (also Gandon) für den Schutz der some,

3 Aspre je soma.

In Casena (Kayseri), 7 Aspre je soma.

In der Karavanserei des Emirs,

2 Aspre je soma.

In der Karavanserei del soldano, 2 Aspre je soma.1

In Gadue, 3 Aspre je soma.

In der Karavanserei di casa Jacomi,

3 Aspre je soma.

Beim Betreten von Sivas aus Richtung Ajas,

1 Aspre je soma.

Drinnen in der Stadt Sivas,

7 Aspre je soma.

Beim Verlassen der Stadt Sivas in Richtung des Fußwegs nach

Täbris, 1 Aspre je soma.

10

In Dudriaga (Todura),

3 Aspre je soma.

In Greboco,

4 Aspre je soma.

In Mughisar für eine Gebühr,

2½ Aspre je soma.

Ebenfalls in Mughisar für den

tantaulaggio, d.h. für die

Bewachung, ½ Aspre je

soma.

Erzincan beim Betreten des Landes in Richtung Ajas,

5 Aspre je soma.

Für einer Gebühr drinnen im Land von Erzincan,

9 Aspre je soma.

Für die Wachen beim Verlassen von Erzincan Richtung Täbris,

3 Aspre je soma.

In der Karavanserei auf dem Berg für eine Gebühr,

3 Aspre je soma.

In Ligurti für eine Gebühr,

2 Aspre je soma.

An der Brücke nach Cantieri für eine Gebühr, 2 Aspre

je soma.4

29

An derselben Brücke für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In der Karavanserei außerhalb von Erzurum Richtung Ajas,

2 Aspre je soma.

In Bagni (Hasankale?) von Erzurum,

1 Aspre je soma.

In Erzurum drinnen im Land für eine Gebühr,

9 Aspre je soma.

In Erzurum das gleiche für ein Geschenk an den Herrn,

2 Aspre je soma.

In Bagni (Hasankale?) von Erzurum Richtung Täbris,

1 Aspre je soma.

In Polorbecch für eine Gebühr, 3 Aspre je

soma.

Ebenfalls in Polarbecche, ½ Aspre

je soma.

In Sermessacalo für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Aggia für den tantaulaggio,3

½ Aspre je soma.

Mitten in der Ebene von Aggio für eine Gebühr,

3 Aspre je soma.

Am gleichen Ort für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Calacresti für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

Bei den drei Kirchen für einen tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

Unter dem Arcanoe für eine Gebühr,

3 Aspre, und für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Scaracanti für den tantaulaggio

½ Aspre je soma.

In Locche für den tantaulaggio

½ Aspre je soma.

Auf der Ebene der Falkner zwei tantaulagi,

in Summe 1 Aspre je soma.

Auf derselben Ebene je Tisch, d.h. je Zeichen des Herrn,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Li Camuzoni (Khamzian?) für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

11

Auf der Ebene Fiume Rosso für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Condro für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Sandoddi für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

In Täbris für den tantaulaggio,

½ Aspre je soma.

Der Zwang der Mongolen, d.h. der tatarischen Schergen,

auf dem Fußweg macht (tocchi) für die soma etwa

50 Aspre aus.

Summe, was eine soma Ware zu Land von Ajas

(Kleinarmenien) nach Täbris (Tartarei) – wie es scheint –

für die oben und zuvor Gestarteten (per le partite di sopra e a drieto) kosten kann:

für alles 209 Aspre die soma.

VII Wie die Gewicht und Maße aus Täbris in diversen Ländern umgerechnet werden (zunächst mit Trapezunt)

Das Gewicht und das Maß von Täbris stimmt mit dem aus Trapezunt überein.

Von Täbris nach Trapezunt dauert es über Land 12–13 Tage für

Waren4 zu Pferd und 30–32 Tage für

eine soma mit der Karawane.

30

100 Saggi von Täbris machen in Trapezunt

93½ saggi.

Man behauptet, dass der Transport von Spezereien von Täbris nach

Trapezunt über Land 27 Bezant

torrisini je

Hundert mene aus Täbris

kostet. Und man sagt, der Transport von Seide von Täbris nach Trapezunt über

Land kostet ¾ (1 weniger ¼) Bezant

torresino die mena. Außerdem sollen die

Transportkosten für 1 soma

Leinen zu 1800–2000 braccia nach dem Maß aus Venedig

von Trapezunt nach Täbris über Land 40 Bezant

torrisini betragen

und darüber hinaus weitere Kosten von 4–5 Prozent. Schließlich wird

behauptet, dass jemand, der mit Waren von Trapezunt nach Täbris gehen will,

die gleichen Fuhrkosten bei1 der passaggio für die soma hat, wie umgekehrt von

Täbris nach Trapezunt.

12 mit Pera und Konstantinopel

100 saggi aus Täbris machen

100¾ saggio.2

100 picchi aus Pera machen in Täbris

140 picchi.

100 mene Spezereien machen in Pera

288 Pfund.

1 mena Seide aus Täbris ergibt in Pera

6 Pfund, 2 Unzen.

1 Pfund Silber nach dem Gewicht von Pera macht

in Täbris 73 saggi.

mit Ajas (Kleinarmenien)

100 mene Spezereien

aus Täbris machen in Ajas 15 ruotoli.

1 mena Seide aus Täbris macht in Ajas

3¾ occhie3.

1 ruotolo = 12 occhie in Ajas

1 Mark Silber nach dem Gewicht von Ajas macht

in Täbris 52 saggi.

mit Famagusta (Zypern)

100 mene Spezerei aus

Täbris machen auf Zypern 40 ruotoli.

1 mena Seide aus Täbris macht auf Zypern 10¼

occhie3.

1 ruotolo

= 12 occhie

1 Mark Silber aus Famagusta macht in Täbris

52 saggi.

mit Venedig

100 mene Spezerei aus

Täbris machen in Venedig 300 leichte Pfund.

1 mena Seide aus Täbris macht in Venedig

6¼ leichte Pfund.

Das Gewicht des Indigo4 aus Täbris macht

in Venedig 125 leichte Pfund.

100 Braccia Leinen nach dem Maß aus Venedig machen

in Täbris 110 picchi.

31

1 Mark Silber nach dem Gewicht von Venedig machen

in Täbris 55½ saggi.

Der Bezant torisino,

so argumentiert man, ist nach kommunalem Wert in Venedig 11

soldi1,

6 Pfennig a grossi (= 11×12+6 = 138

Pfennig a grossi) aus Venedig.

1 Grosso =

26 Pfennig a grossi in Venedig

mit Genua

100 mene Spezerei aus

Täbris machen in Genua 288 Pfund.

1 mena Seide aus Täbris macht in Genua

6 Pfund und 2 Unzen.

Das Gewicht des Indigo aus Täbris2

macht in Genua 120 Pfund Indigo netto.

73 saggi aus Täbris machen in Genua

72 saggi che sind 1 Pfund in

Genua.

13

100 canne Leinen aus Genua machen in Täbris

550 picchi.

Trapezunt

- Gebühren, die man in Trapezunt bezahlt

- Wie das Gewichte und das Maß aus Trapezunt in gewissen Ländern umgerechnet werden; zunächst mit Pera und Konstantinopel

- mit Venedig

- Geld:

- Aspre, perperi

- Gewicht:

-

1 Pfund bzw. ruotoli =

15 Unzen (schweres Gewicht)

Silber: leichte Pfund - Raummaß:

- soma

- Länge:

- picchio

Das Gewicht und das Maß von Trapezunt sind dieselben wie in Täbris.

Alle groben Spezereien verkauft man in

Trapezunt nach schweren Pfund,

d.h. nach ruotoli.

Alle feinste Spezereien werden in

Trapezunt nach schweren Unzen verkauft.

1 Pfund =

15 Unzen3 (schweres Gewicht)

Tuch wird in Trabzon nach picchio verkauft.

Silber verkauft man in Trapezunt nach leichten Pfund.

Gebühr, die man in Trapezunt bezahlt

Wer Ware nach Trapezunt bringt oder es an Einwohner im Land verkauft, bezahlt

an den Kaiser von Trapezunt 3 Prozent. Wenn man jedoch an Genuesen oder

andere lateinische Personen verkauft, so bezahlt man nichts.

Wenn du die Ware, die du nach Trapezunt mitgebracht hast, nicht in

Trapezunt verkaufen willst, sondern mit ihr nach Täbris gehen –

oder richtig es versenden – willst, bezahlst du dem Kaiser

28 Aspre je soma und außerdem

1 Aspre je soma an den Konsul.

Wer mit Waren von Täbris nach Trapezunt kommt, bezahlt in Trapezunt

15 Aspre je soma

so viel für Spezerei wie für jede andere Ware, gleich welcher Art,

14 Aspre an den Kaiser und

1 Aspre an den Konsul.

Wie das Gewicht und das Maß aus Trapezunt in gewissen Ländern umgerechnet werden (zunächst mit Pera und Konstantinopel) 4

1 ruotoli aus Trapezunt macht in Pera

15 Pfund.

Man behauptet, dass die Fracht für Waren von Pera nach Trapezunt

32

in einer bewaffneten Galeere 1½ perperi der

Ballen Leinen kostet; bei Spezereien zahlt man von

Trapezunt nach Pera in einer bewaffneten Galeere 1½

perperi je genuesischen cantar.

Seide und goldene Stoffe kosten ½–¾ Prozent. Im

unbewaffneten Segelschiff [[zahlt man]] die Hälfte weniger.

14 mit Venedig

25 venezianische Pfund machen in Trapezunt

[...] Pfund

25 venezianische schwere Pfund machen in Trapezunt

[...] Pfund

25 schwere Pfund aus Trapezunt machen in Venedig

1 carica.

1 carica = 400 leichte

Pfund in Venedig

11 venezianische Unzen Silber machen in Trapezunt

1 leichtes Pfund.

VIII Konstantinopel und Pera

- Einteilung, wie die Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera gehandelt werden . . .

- Nach der cantara werden verkauft

- Was nach Hundert in Konstantinopel und Pera verkauft wird

- Was nach Pfund, d.h. nach zehn Pfund, in Konstantinopel und in Pera verkauft wird

- Zu je zehn Stücken werden verkauft

- Stückweise werden verkauft

- Zu Hundert picchi aus Khazaria verkauft man

- Konstantinopel und Pera: Länge der Stoffe

- Das hier verwendete Geld

- Gebühren an den Zoll des Kaisers, die man in Konstantinopel auf Waren bezahlt, die von Händlern hier angeboten oder exportiert werden

- Hinweis auf verschiedene Weizensorten in Konstantinopel und Pera und deren Unterschiede im Wert

- Welche Sorten Alaun man in Konstantinopel und Pera hat

- Welche Preise und Sorten Wachs es in Romania und am Schwarzen Meer gibt, die in Pera und Konstantinopel münden; das bulgarische Wachs ist das beste, das aus diesen Orten (also Romania) stammt

- Wiegegebühren für Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera

- Worauf man Steuern bezahlt

- Was man den Maklern von Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera bezahlt

- Gebühr für das Verpacken von Ballen (balla oder pondi) in Konstantinopel und Pera

- Kosten für den Käufer von Weizen oder anderem Getreide

- Kosten für Wollstoffe in Konstantinopel und Pera

- An die Empfänger von Olivenöl aus dem Westen in Konstantinopel, denn der größte Teil wird in Konstantinopel deklariert: Über die Ausgaben für Olivenöl in Konstantinopel und Pera

- Kosten für Leder in Konstantinopel und Pera

- Ausgaben für Weine aus dem Westen in Konstantinopel und Pera

- Konstantinopel und Pera: Wie das Gewicht und das Maß dieser Städte in mehreren Gebieten umgerechnet werden. Zunächst für Genua und Pera

- mit Marseille (Provence)

- mit Nîmes und Montpellier

- mit Avignon

- mit Nizza (Provence)

- mit dem ebenen Apulien

- mit Venedig

- mit Neapel (Landschaft Terra di Lavoro)

- mit Sizilien

- mit Ancona

- mit Pisa

- mit Cadiz (Spanien)

- mit Sevilla (Spanien)

- mit Casablanca (Spanien)

- mit Brügge (Flandern)

- mit London (England)

- mit Asow am Schwarzen Meer

- mit Feodossija am Schwarzen Meer

- mit Tunis (Barbarei)

- mit Lucca

- mit Cava (Königreich Neapel)

Konstantinopel gehört zu Griechenland, Pera (etwa Galata) aber zu Genua.

Ihre Maßeinheiten sind im Prinzip nicht identisch.

- Geld:

-

1 perpero (Gold) = 12 Grosso

= 24 Karat

1 Grosso (Silber) = 2 Karat

stanmini (Kupfergeld)

1 Grosso = 8 tornesi Kleingeld = 32 stanmini

1 tornese Kleingeld = 4 stanmini - Gewicht (zu den Angaben in Gramm basierend auf dem Tari zu etwa 0,883g siehe hier):

-

1 cantaro = 150 Pfund (Genua)

1 Hundert = 100 Pfund (Genua)

100 schwere Pfund = 140 leichte Pfund

1 Pfund = 1½ sommo = 12 Unzen = 72 saggi = 1728 Karat

1 sommo = 8 Unzen = 48 saggi = 1152 Karat

1 Unzen = 6 saggi = 144 Karat

1 saggio = 24 Karat = 1 perpero = 1 peso

100 perperi (Pera) = 99 perperi, 8 Karat (Konstantinopel)

1 schwerer migliaio = 11 cantara, 11 ruotoli in Genua

1 Pfund ≈ 317,09g, 1 Unze ≈ 26,42g, 1 saggio ≈ 4,40g (Konstantinopel)

1 Pfund ≈ 312,58g, 1 Unze ≈ 26,05g, 1 saggio ≈ 4,35g (Pera)

- Raummaß:

-

Haselnüsse, Salz, Weizen:

1 Scheffel (moggio) = 4 quarte = 8 pedalitre

1 quarta = 2 pedalitre

56½ Scheffel aus Konstantinopel = 60 Scheffel aus Pera

Olivenöl: mena, laina (je nach Quelle saina), Tonkrug, metro - Länge:

- Leinen: picchi

Einteilung, wie die Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera gehandelt werden und welche Kosten sie verursachen — insbesondere jedoch in Pera, weil man den größeren Teil colàe der Waren in Pera herstellt und außerdem gibt es hier ständig mehr Händler.

Der andere Teil – also Konstantinopel – gehört den Griechen,

nur Pera ist frei, denn Pera gehört den Genuesen. Von Konstantinopel nach

Pera sind es 5 Meilen über Land und eine halbe Meile über das Meer.

In Konstantinopel und Pera gibt es mehrere Arten Gewichte und Maße, die

sich wie nachstehend unterteilen lassen:

Der Tausend (migliaio) grosso entspricht

11 cantari und 11 ruotoli genuesisch.

In Genua gilt

1 cantaro = 150 Pfund.

1 Hundert = 100 Pfund

1 Pfund3 = 72 saggi (= 12 Unzen).

1 Saggio = 1 perpero = 24 Karat = 1 peso;

1 Hundert = 100 Pfund

1 Pfund3 = 72 saggi (= 12 Unzen).

1 Saggio = 1 perpero = 24 Karat = 1 peso;

1 Scheffel (moggio) = 4 quarte

= 8 pedalitre

1 quarta = 2 pedalitre

1 quarta = 2 pedalitre

100 perperi nach dem Gewicht von Pera sind in

Konstantinopel nur 99 perperi und 8

Karat

1 perpero =

24 Karat5

33

15 Nach dem cantara werden verkauft

Indigo aus Bagdad wird nach Gewicht verkauft,1

wobei das Gewicht2

als cantaro zu verstehen ist.

Wenn der Käufer es ungewogen vom Verkäufer will und es dann mehr oder weniger

ein cantaro ist, geht das Zu Gunsten oder zu Lasten

des Käufers. Aber man wiegt quasi für alle und sie bezahlen so viel, wie es

wiegt, in der Tat zahlt man mehr oder weniger das, was der Höhe des

cantare entspricht. Auch sind das Leder und die

Verpackung im Indigo eingeschlossen, ohne Tara zu nehmen und ihne das Indigo

zu prüfen; das Indigo ist nicht zu sehen, außer durch ein kleines Loch,

aus dem eine Probe zur Inspektion entnommen wird. So ist es der Brauch an

diesen Orten.

Bei Wachs, auch wenn es Verunreinigungen4

enthält, wird durch die

taratori

in Pera Tara genommen; Wermut; bei Krapp gibt man den zugehörigen Sack,

ohne Tara zu nehmen; Alaun von jeder Art – selbst Aulaunstein

– ist im Sack verschnürt, wobei Sack und Strick im Alaun enthalten

sind.

Rindsleder, Büffelleder, Pferdeleder: Wenn du sie kaufst, zeigst du sie

den cernitori,

die in (sopra ciòe in)

Pera sind, und wenn sie sich feucht

oder nass anfühlen, veranlassen sie, dir einen angemessenen Schadensersatz zu

geben. So lautet die Verfügung in Pera und Konstantinopel; sie werden

nicht in die Sonne gelegt, außer sie wären unangemessen nass.

Talg in Krügen, Eisen, Zinn und Blei von jeder Art.

Zibibbo, d.h. getrocknete Weintrauben und Rosinen von jeder Art:

Man gibt die Matten für die Rosinen, ohne Tara zu nehmen, es sei denn, die

Rosinen kommen aus Syrien, hier nimmt man die Tara der Tasche oder richtiger

des Korbs und beides verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Seife aus Venedig, Ancona und Apulien in Holzkisten: Man nimmt die

Tara der Kisten und nachdem man das gemacht hat, verbleiben die Kisten

kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Seife aus Zypern und Rhodos ist eingesackt und man gibt die Seife

einschließlich des Sacks, ohne Tara zu nehmen.

Zerkleinerte und in Säcken abgefüllte Mandeln werden einschließlich

Sack abgegeben, es sei denn sie haben mehr als einen Sack oder ein Seil.

16

Damit der Käufer nichts vom Verkäufer hat außer dem Sack für die Mandeln

(weder den anderen Sack noch das Seil), entfernt man sie und wiegt sie mit

den Mandeln. Nun nimmt man die Tara (der zusätzlichen Verpackung) und das Seil

verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

34

Honig

abgefüllt in Schläuchen: Man nimmt Tara des Fasses oder des Schlauches,

nachdem man das gemacht hat, verbleiben das Fass oder besser der Schlauch

beim Käufer kostenfrei.

Baumwolle mapputo: Man gibt den Sack als Baumwolle ohne Tara.

Baumwollgarn: Man nimmt Tara für den Sack und der Sack verbleibt

kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Reis: Man gibt den Sack als Reis, wenn er verschnürt ist, nimmt man

Tara des Seils und das Seil verbleibt beim Verkäufer.

Türkischer Gallapfel von jeder Art: Wenn er im Sack ist, wiegt man

ihn mit dem Sack und man gibt den Sack mit dem Gallapfel, ohne Tara zu nehmen.

Getrocknete Feigen aus Mallorca und Spanien in Tüten.

Auripigment: Der Sack zählt als Auripigment.

Fäberdiestel: Man nimmt Tara des Sacks und des Seils. Danach verbleiben

der Sack und das Seil beim Käufer kostenfrei.

Henna: Der Sack wird als Henna mitgegeben, nur beim

sommo – so ist es der Brauch – nimmt

man 4 Prozent Tara.

Kreuzkümmel: Der Sack wird als Kreuzkümmel mitgegeben. Wenn er mit

einem Seil verschnürt ist, nimmt man Tara und das Seil verbleibt

kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Pistazien: Man gibt mit ihnen den Sack und nimmt keine Tara, außer sie

haben mehr als einen Sack je Ballen, dann nimmt man Tara der zusätzlichen

Säcke und der eine verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Schwefel: Für den Sack oder die Tonne, in dem er ist, nimmt man Tara,

danach verbleibt der Sack bzw. die Tonne kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Kasie: Man nimmt die Tara des Sacks und der Sack verbleibt beim Käufer.

Pech: Man nimmt Tara der Matte und die Matte verbleibt beim Käufer.

Bleiglätte (Farbe): Der Sach wird mitgegeben, ohne Tara zu nehmen.

Pökelfleisch, Käse.

17

Leinen aus Alexandria: Man gibt den Sack als Leinen, es sei denn

4 Prozent sind beschädigt, dann verbleibt der Sack kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Leinen aus Romania: Den Sack gibt man als Leinen, ohne Tara zu nehmen.

Mohair: Man nimmt Tara des Sacks und der Sack verbleibt beim Käufer

kostenfrei.

Gewaschene und schmutzige Wolle aus Romania, schmutzige und gewaschene

Wolle aus der Türkei: Der Sack gilt als Wolle, ohne Tara zu nehmen.

Kastanien: Man gibt den Sack als Kastanien ohne Tara.

Was nach Hundert (centinaia) in Konstantinopel und in Pera verkauft wird

Runder Pfeffer und versteuert; Ingwer und versteuert.

Geschältes Rotholz: Man gibt es verschnürt mit einem Seil aus Gras (erba),

für das man Tara nimmt.

35

Schellack nicht versteuert;

Zitwer

und versteuert.

Weihrauch und versteuert.

Zucker und Puderzucker von jeder Art: Für die Kiste bzw. das Fass, in

dem sie sind, nimmt man Tara und die Kiste bzw. das Fass verbleiben

kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Aloe von jeder Art: Von dem Leder, in dem die Aloe ist, nimmt man Tara

und das Leder verbleibt beim Käufer kostenfrei.

Quecksilber wird mit Bachile,

Leder und Seil gewogen, danach nimmt man Tara für den Bachile, das Leders

und das Seils,1

sie verbleiben kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Röhren-Kassie: Man nimmt Tara der Matte2,

und danch verbleibt sie beim Käufer kostenfrei.

Salmiak: Man liefert weder einen Sack, noch eine Holzkiste mit.

Zinnober, Zimt und versteuert.

Galbanum und versteuert.

Ladanum aus Zypern: Man gibt

den Sack für das Ladanum

zum (a) Gewicht.

Mastix und versteuert: Für die Steuer und den Korb wird Tara genommen,

die Steuer übernimmt der Verkäufer und der Korb geht an den Käufer.

Kupfer: Wenn man es mit der Tonne wiegt, nimmt man Tare der Tonne,

danach geht die Tonne kostenfrei an den Käufer.

Große, mittlerer oder kleiner Amber, unbearbeitet: Der Verkäufer gibt

dem Käufer kostenfrei entweder die Holzkiste oder den Sack, es sei denn,

der Amber hätte ein weiteres Seil oder eine andere Verpackung, dann

verbleibt das Seil oder die Verpackung beim Verkäufer.

18

Korallen mit Rinde und versteuert: Weil sie einen gewissen Abfall

enthalten, vesteuert man sie, damit sie sich von der einhüllenden Rinde

hervorheben. (che se ne spicca per lo involgere che se ne fa)

Gereinigte Koralle sowie mittlere und kleine concio:

Der Käufer àe dem Verkäufer für die Art des Amber.

[[ambra concia = Bernstein?]]

Was nach Pfund, d.h. nach zehn Pfund, in Konstantinopel und in Pera verkauft wird

Rohseide von jeder Art: man wiegt sie nach bilancia

picciola (kleine Waagen oder leichtes Gewicht)

zu vier Zehnern auf einmal und nicht mehr. Der

Verkäufer gibt dem Käufer die miccia (Schutzhülle?), in

der sie eingepackt ist, und das Seil kostenfrei. Alle anderen Verpackungen

bleiben beim Verkäufer. Der Käufer muss dem Knappen (fante) des Verkäufers

4 Karat5

pro Ballen Seide für Wein4 geben.

36

Safran von jeder Art und Nelkenstängel.

Gewürznelken und versteuert; und Kubebenpfeffer (cubelibe) von jeder Art

und versteuert.

Legnio [Aloe1];

Rhabarber und versteuert; Mazis und versteuert.

Langer Pfeffer; Hohes Zyperngras und versteuert; gebrochener Kampfer.

Muskatnuss und versteuert; Gewürz-Lavendel und versteuert.

Kardamom von jeder Art und versteuert.

Orientalische Purgierwinde, zerstoßene

Perlen, Manna, Borax (Mineral), Gummiarabikum.

Drachenblut, Kamelgras,

Turbith,

Sendal-Seide von jeder Sorte.

Konfekt von jeder Art, Goldgarn von jeder Art.

gekochte Seide von jeder Art.

Amber [[ wohl Bernstein]] bearbeitet nach Art paternostri

(unseres Vaters) oder auf andere Weise verarbeitet, so dass sie mit einem

Loch versehen und aufgefädelt sind: Man nimmt Tara des Drahts.

Alle anderen feinen und feinsten Spezereien werden hier ganz ähnlich nach

leichten Pfund verkauft. Der Sack, die Verpackung

oder ein anderes Gefäß, in dem die besagten Dinge sind,

verbleiben beim Käufer kostenfrei, nachdem Tara genommen worden ist.

Gold oder Silbergarn aus Lucca, Genua oder der Provence werden hier nach

Hundert verkauft, also nach der Art wie es in Lucca

verkauft wird.

Feine Perlen werden hier nach dem Gewicht des Pfund,

der Unze, des saggio oder

des Karats verkauft, je nach ihrer Größe und Güte.

Zu je zehn Stücken werden verkauft

Steifleinen (Buckram) aus Erzincan und Zypern: Die Holzkiste, in der

sie sind, verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

19 Stückweise werden verkauft

Samt aus Seide, Camocas,

Marramas,

goldene Stoffe von jeder Art, Nacchetti von

jeder Art, Nacchi von jeder Art und ähnlich goldene Stoffe oder Seide

außer Sendal-Seide.

Kamelott stückweise, je nachdem, ob es groß oder klein ist.

Zu Hundert picchi aus Khazaria verkauft man

Leinen, canovacci von

jeder Art, außer Leinen aus der Champagne, sie werden verkauft, wie wir unten

schildern werden. Der Verkäufer gibt3

das Seil und das grobe

Tuch, in dem der Ballen eingewickelt ist, dem Käufer kostenfrei.

Die Wollverpackung im Ballen rechnet der Verkäufer dem Käufer zu, worüber

sie sich gemeinsam einigen können.

37

Tuch aus der Champagne wird stückweise verkauft, man geht davon aus, dass der

Stoff(ballen) 42½–43 picchi aus

Khazaria

enthält, sodass man bei 2⅓ Stück sagt, sie halten 100

picchi aus

Khazaria.

Der Käufer erhält vom Verkäufer das Seil und die Verpackung wie bei den anderen

Leinen und canovacci.

Fränkische Stoffe oder Stoffe „von jenseits der Berge” werden stückweise,

nach livrate (Livre) oder nach Real verkauft. Wenn man sie nach livrate

(Livre) oder Real verkauft, gibt man die Stoffe, ohne zu messen, so wie sie

eingekerbt sind; es sei denn, auf dem Stoff wären einige Kürzen eingezeichnet,

dann macht der Verkäufer neue Kürzen für den Käufer, die dort eingekerbt oder

markiert würden. Wenn man dagegen stückweise verkauft, also weder nach Livre

(livrate) noch nach Real, so gebührt es sich, dass der Verkäufer dem Käufer

bei jedem Stoff(ballen) so viele picchi macht, wie es

für das Land, wo der Stoff hergestellt worden ist, üblich ist. Dies wird in

dem vorliegenden Buch genau ausgeführt. Sollte zu wenig vorliegen, ist

der Verkäufer verpflichtet, das dem Käufer bis zur Vollendung seiner Länge

zu entschädigen; sollte es jedoch zu viel sein, was hier nicht zu Fuß

geschrieben ist, wäre der Zusatz für den Käufer kostenlos. Der

picco, nach dem man die Stoffe misst, ist ein

picco für Leinen per sè; er ist kleiner als der

picco aus

Khazaria,

nach dem2

man Tuche misst, so viel dass 1½ picchi

Wollstoffe einen picchi aus

Khazaria

machen;

12 canne aus Florenz machen

50 picchi nach diesem [[Maß]] für Stoffe.

20 Konstantinopel und Pera: Länge der Stoffe

| Châlons sur Marne | 44 | picchi |

| Tournai | 54 | picchi |

| Beauvais | 48 | picchi |

| Bagnuolo (Bagnols-sur-Cèze?) | 43 | picchi |

| Castellonovo | 66 | picchi |

| Paris | 60 | picchi |

| St. Denys | 54 | picchi |

| Toulouse | 44 | picchi |

| Narbonne | 44 | picchi |

| Carcassone | 44 | picchi |

| Béziers | 44 | picchi |

| Perpignan | 44 | picchi |

| Montolieu | 44 | picchi |

| Brüssel | 54 | picchi |

| Mecheln | 44 | picchi |

| Löwen, della picciola magione | 32 | picchi |

| Löwen, della gran magione | 44 | picchi |

| Brügge | 44 | picchi |

| Vergati/Gestreifte aus Gent | 46 | picchi |

| Vergati/Gestreifte aus Poperinghe | 44 | picchi |

| Coverture aus Ypern5 | 44 | picchi |

| Tritane | 44 | picchi |

| Weiße aus Narbonne | 22 | picchi |

| Weiße aus Bagnuolo (Bagnols-sur-Cèze?) | 42 | picchi |

| Antwerpen | 42 | picchi |

| Venedig | 40 | picchi |

| Mailand | 44 | picchi |

| Como | 44 | picchi |

| Florenz | 48 | picchi |

38

Florentinische Stoffe werden nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

Karat1

der soldo der Währung der canna verkauft.

D.h., wenn (1) die (florentinische) canna auf

dem Stoff gekennzeichnet ist, (2) der Preis

40

soldi des Florin gilt und (3)

der Verkaufswert nach dem Wechselkurs von

15 Karat1

je soldo des Florin festliegt, dann

multipliziert man 15 Karat4 mit 40, macht 600

Karat.4

1 perpero = 24 Karat

Das ergibt umgerechnet 25 perperi. Also kommt der

Stoffballen zu 40 soldi zum Florin

auf 25 perperi die canna.

Der Stoff muss 12 canne aus Florenz halten,

das ergibt 48 picchi,

und wenn es weniger als 48 picchi sind,

muss der Verkäufer dem Käufer [[alles]] bis zur

21

Summe von 48 picchi erstatten. Sind es jedoch mehr

als 48 picchi, zählt man das mehr oder weniger, als

wären es 48 picchi.Beim Verkauf von Stoffe in großen Mengen, sofern der

Käufer den Ballen verschnürt vorfindet, gehören die Verpackung und das Seil

für den Ballen dem Verkäufer und das Hauptseil im Inneren [[ist]] umsonst.

Wenn der Kunde aber kommt, um die Stoffe zu inspizieren, und er findet den

Ballen von außen aufgeschnürt vor, darf er das Hauptseil im Inneren nicht

kostenlos behalten. Wenn die Stoffe eine

bandinelle

haben und der Käufer sie so vorfindet, muss er die

bandinelle mit den Stoffen

nehmen, aber nicht mehr.

Krudes Feh, Fehbäuche und Fehrücken sowie Eichhörnchen aus Slawonien

werden nach Tausend verkauft

(1030 Stück = 1 Tausend).

Eichhörnchen aus Apulien werden zu Hundert

(100 je Hundert) verkauft.

Marder und Wiesel werden zu Hundert (100 je

Hundert) verkauft, es sei denn, sie werden durch die

oben genannten Inspekteure der Gemeinde von Pera gesichtet: Wenn man

unzulässige (strafbare) hat, gibt man zwei unzulässige für eine gute; und je

nachdem wie die guten und unzulässigen sind, gibt man manchmal mehr oder

weniger.

Ziegenleder, d.h. Leder von Ziegen oder Hammeln, werden nach dem Wert von

soundso vielen perperi der Hundert

verkauft; und wenn es notwendig ist, Tara zu nehmen, nimmt man sie.

Wer einen ganzen Ballen kauft, der erhält das Seil, mit dem er verschnürt ist,

kostenlos.

Mandeln in der Schale werden nach der Zahl und nach dem Wert von

soundso vielen Tausend Mandeln je

perpero verkauft, so wie es der Verkäufer und der

Käufer vereinbaren.

Datteln werden nach Tausend an der Zahl verkauft

und der Korb verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Haselnüsse werden nach Scheffel (moggia) entweder aus Pera

oder Konstantinopel gemäß Abmachung verkauft.

Der Hundert Haselnüsse aus Neapel ergibt in

Konstantinopel 56½ Scheffel und

in Pera 60 Scheffel. Wenn der Verkäufer sie für den

Käufer abmisst, gibt er den Sack aus grobem Tuch,

in dem sie sind, kostenlos mit.

Walnüsse werden nach Zahl und nach dem Wert von soundso

vielen Tausende der perpero verkauft.

39

Gesalzener Stör wird nach Tausend an

der Zahl verkauft, d.h. genau 1000 für Tausend, und man

vereinbart Bedingungen zu d'aroti und jede andere Form

schlechter Qualität (malitia).

Salz wird nach Scheffel, dem Maß für Getreide,

verkauft.

Klares und gelbes Öl aus Venedig oder Marken, Olivenöl aus Apulien,

Gaeta oder jedem anderen Teil, das in Fässern umläuft, wird nach dem Wert

von soundso vielen perperi1

das Fass des „½ Tausend” aus Apulien bzw. nach

botte di mena aus Neapel verkauft.

22

Das Fass des „½ Tausend” muß 57 laine

2

enthalten, während die botte di mena aus Neapel

(≈501,051l) 76 laine umfassen muss.

Wer nach Fass verkauft, muss so viele laine machen,

wie ein Fass Wein an den Orten, wo du es verkaufst, enthält.

Beim Verkauf nach Fass verbleibt das Fass kostenfrei beim Käufer,

wenn aber nach laine und nicht nach Fass verkauft wird,

verbleibt das Fass beim Verkäufer und nicht beim Käufer.

Fast alles – insbesondere im Großhandel – wird hier nach Fass

verkauft, nur im Kleinen wird nach laine

und nach dem Wert von soundso vielen Karat

je laina verkauft.

Alles andere Olivenöl, das in Krügen

hierherkommt, wird nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

perperi1

der Krug verkauft. Der Krug muss

bis zur Bleiglätte voll sein. Bei zu kleiner Menge füllen sie ihn auf. Der

Tonkrug bleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer. Man sagt,

der Tonkrug aus Sevilla enthält 8¼–8½

laine.

Weizen, Gerste, alle Getreidesorten und Hülsenfrüchte

werden hier nach Scheffel und nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

Aspre der Scheffel

entweder aus Pera oder aus Konstantinopel verkauft.

1 Scheffel (moggio) = 4 quarte

= 8 pendaltre

1 quarta = 2 pendaltre

Man verkauft im Kleinen nach Scheffel,

quarte, pendaltre oder halbe

pendaltre, wie die kleinen Leute es wollen.

Der Scheffel aus Konstantinopel ist um

6–7

Prozent größer als der aus Pera.1 quarta = 2 pendaltre

Griechischer Wein wird nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

perperi die botte di mena aus

Neapel verkauft. Man behauptet, dass sie 48 metri

enthält, und wenn es zu wenig wäre (fusse sc(i)ema), füllt es der

Verkäufer dem Käufer auf. Das Fass verbleibt kostenfrei beim Käufer.

Wein aus Tropea (Kalabrien), Patti (Sizilien) und

Pescia3 (Apulien) wird hier auf die

griechische Art verkauft.

Wein aus Cotrone (Kalabrien) wird hier nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

perperi das Fass verkauft, und man transportiert den

Großteil in Fässen, die man von Venedig nach Cotrone bringt und die ein

Fassungsvermögen von [...] Bütten aus Venedig haben. So ein Fass muss

45 metri Wein nach dem Maß aus Konstantinopel enthalten.

Wenn es weniger enthält, ist der Verkäufer verpflichtet, es dem Käufer

bis zu 45 metri aufzufüllen. Es sei denn, der Verkäufer

hätte dem Käufer gesagt: „Ich verkaufe es, wie es ist, so viel oder

wenig es auch enthält”, dann ist er dem Käufer nicht verpflichtet, es neu zu

vermessen und ihn zu entschädigen. Wenn er das aber nicht zu ihm sagt,

stimmt er nur zu, dass er ihm 45 metri in einen Teil

eines Fasses (il frusto

della botte) seiner Wahl abfüllt. Schließlich verbleibt das Fass beim

Käufer kostenfrei.

40

Wein aus Marken wird im Fass oder in Fässchen, so wie sie sind, verkauft.

Wein aus Kreta verkauft man nach hundert

metri und nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

perperi der hundert

metri, und man misst [[was?]]; das Fass verbleibt

beim Käufer kostenfrei.

23

Wein aus Romania bassa

wird hier ebenfalls wie der aus Kreta verkauft.

Wein des Landes verkauft man hier nach dem Wert von soundso vielen

perperi der hundert

metri. Wenn er in Fässern ist, verbleibt das Fass beim

Verkäufer kostenfrei. Wenn er jedoch in einem Krug

ist, gehören die Krüge dem Käufer. [[seltsam: Käufer

und Verkäufer vertauscht?]] Manchmal verkauft man auch

nach hundert Krügen.

Das hier verwendete Geld

In Konstantinopel und Pera werden mehrere Arten Geld verwendet, was sie

zuallererst bei allen Zahlungen für Waren verwenden. Man gibt bei Zahlung

nach peso di bilance ein Goldgeld, das

perperi genannt wird. Diese halten eine Legierung von

11 Karat Feingold je Unze

und der Rest der Legierung bis zu 24 Karat

enthält 6 Karat Feinsilber und 7 Kupfer

je Unze. Bei Zahlungen gilt

1 perpero = 24 Karat

und ähnlich zum perpero zählt man je ein

saggio Gewicht

1 saggio = 1 perpero Gewicht.

Folglich muss jemand 100 perperi haben, um 100

saggi Gewicht auf einer Waage auszugleichen. Auf der

anderen Waage gibt man so viele Stücke perperi Gold,

die dasselbe Gewicht der 100 saggi ergeben.

Wenn man also eine Zahlung für eine kleinere oder größere Summe

perperi machen müsste, gäbe man auf diese Weise

weniger oder mehr Gewicht des saggi auf die Waage,

sodass man die Zahlung der perperi nach Gewicht und

nicht als Buchungszahl macht.

Im Kleinen verwendet man an den oben genannten Orte ein Silbergeld,

wovon 12 auf einen perpero gehen. Sie haben eine

Legierung von [...] Unzen Feinsilber je

Pfund.

1 Grosso = 81

tornesi Kleingeld.

Außerdem gibt es ein weiteres Geld, das ganz aus Kupfer ist und

das sie stanmini nennen.

1 tornese Kleingeld = 4 stanmini

Allerdings macht man von diesen stanmini keine

Zahlungen, es sei denn für die passaggio

Konstantinopels durch das Land sowie für Kräuter und kleine Dinge.

Daneben verwendet man auch den

Grosso aus Venedig. Davon

gehen 12½–13 auf den perpero, je nachdem

wie teuer das Silber ist. Man rechnet diesen Grosso aus Venedig zu 8

Pfennig tornesi Kleingeld, ganz so wie oben den großen

Grosso des perpero.

Stücksilber wird an den oben genannten Orten je Pfund verkauft.

Ihren größten Teil, wenn man daraus sommi Silber macht,

was eine Legierung von 11 Unzen und 17

Pfennig Feinsilber je Pfund hält,

41

bringt man als sommi auf die Krim und bis nach

Kathay (nördliches China). Diese sommi sind

Stangensilber, die zwar nicht vom gleichen Gewicht sind, aber sie liegen

mehr oder weniger in einem Intervall, dabei eine kann alles in allem

[...] Unze wiegen.

24

Massives Gold in Stangen, Gold 23½ Karat fein

und Tanga-Gold werden in Konstantinopel und Pera

nach saggio und für soundso viele

Karat je saggio Gewicht

verkauft.

Gebühren an den Zoll des Kaisers, die man in Konstantinopel auf Waren bezahlt, die von Händlern hier angeboten oder exportiert werden

Genuesen und Venezianer bezahlen weder für den Eintritt noch für das

Verlassen.

Pisaner bezahlen für alle Waren, die sie in Konstantinopel anbieten,

2 Prozent auf den Warenwert in Konstantinopel, ohne die für die Waren

gemachten Ausgaben abzuziehen (abatterne); zusätzlich sind 2 Prozent für

das, was sie davon exportieren, zu zahlen. Von dem, was sie exportieren,

sind sie nicht gezwungen zu bezahlen, außer sie exportieren es nicht.

Sie bezahlen das gleiche in Pera.

Florentiner, Personen aus der Provence, aus Ancona, Katalanen, Sizilianer

und alle anderen Fremde bezahlen 2 Prozent <beim Eintritt und

2 Prozent>1 beim

Verlassen auf den Warenwert. Außerdem sind sie gezwungen,

gleichzeitig Eintritt und Austritt zu bezahlen. Dann sind sie Herren

(signori), die exportieren, wann sie es wollen, ohne eine andere Gebühr zu

bezahlen; es sei denn das eingenommene Geld lässt sich nicht beim Handeln

zum Kaufen oder Weiterverkaufen auf dem Land verwenden, wenn also nicht

für den Export gekauft wird (Verkauf außerhalb der Stadt, aber im Inland, also

kein Export). Wenn man aber einkauft, um es auf dem Land weiterzuverkaufen,

zahlt man für jeden den Einkauf oder Verkauf auf dem Land 2 Prozent.

Wenn sie über See zum Schwarzes Meer fahren, dann bezahlen sie bei ihrer

Rückkehr auf das, was sie mitbringen 2 Proozent, aber nicht mehr.

Wenn man die Gebühr an den Zoll bezahlt, erhält man eine vom

Zollbeamten handgeschriebene Bescheinigung. Wenn man nichts in der Zeit

dieses Zollbeamten exportiert – er bleibt ein Jahr, aber nicht

länger, im Büro –, dann kann man später immer noch exportieren.

Denn in der Zeit eines anderen Zollbeamten, der zu dieser Zollstation

kommt, zeigt man ihm die Bescheinigung, dass man bereits für den Eintritt

und den Austritt an einen vorherigen, anderen Zollbeamten gezahlt hat.

42

Man sollte tunlichst daran denken, dass jemand, der den Zollbeamten

(wie auch den Schreibern und den türkischen Männer) Ehre erweist und ihnen

einige Dinge oder Geld überlässt,

25

sehr zuvorkommend passieren darf; sie beurteilen (ragionano) die

angebotenen Waren ständig niedriger, als sie wert ist.

Hinweis auf verschiedene Weizensorten in Konstantinopel und Pera und deren Unterschiede im Wert

Weizen aus Tekirdağ ist Weizen, der aus dem Griechenland Konstantinopels stammt;

er ist der beste Weizen aus Romania; er wird ständig 6–8

Karat1 der

Scheffel teurer verkauft als der aus Feodossija,

sodass Weizen aus Feodossija dem aus Tekirdağ nahe kommt.

Weizen aus Feodossija ist der beste am Schwarzen Meer und in

Khazaria;

er ist 2–4 Karat2 je Scheffel

mehr wert als der aus Lifetti am Schwarzen Meer, so dass jeder Weizen

vom Schwarzen Meer so viel wert wie der aus Feodossija, außer dem

geringwertigeren aus Lifetti.

Weizen aus Anchialos hat quasi den gleichen Wert wie der aus Feodossija

und er unterscheidet sich fast nicht von dem anderen.

Dennoch würde man immer schneller einen Käufer für den aus Feodossija, als

für den aus Anchialos finden.

Weizen aus Maurocastro

kommt hinter dem aus Anchialos. Beide haben fast den den gleichen Wert.

Obwohl der aus Anchialos nicht besser ist, ist er sicherlich

leichter absetzbar und besser auf Seefahrten zu erhalten.

Weizen aus Varna, Bulgarien, Vezina und Sosopol ist schlechter

als die oben genannten Sorten. Er hat immer einen um 12–14

Karat5 je

Scheffel schlechteren Wert als der aus Tekirdağ

bzw. 6–8 Karat je Scheffel als der aus Feodossija

bzw. Khazaria

am Schwaren Meer. Die Weizensorten der Orte wie Varna, ganz Bulgarien,

Vezina und Sosopol haben alle einen Preis, wobei Romania dem Namen nach

keine anderen Weizensorten hat.

Gerste aus Tekirdağ ist 4 Karat8

je Scheffel mehr wert als der von Feodossija

und der aus Feodossija ist 2–3 Karat je

Scheffel mehr wert als der aus Varna.

Hier und heute findet das hingegen keine weitere Erwähnung.

43

26 Welche Sorten Alaun man in Konstantinopel und Pera hat

Alaunstein (Alunit) aus Koloneia ist das beste Alaun

und das beste, was in der Levante und im Lateinischen Kaiserreich

(Romania) verarbeitet wird. Es ist 12–15 Karat

je cantaro mehr wert als Alaun di Sorte des guten

Luminiera.

Alaun des guten Luminiera kommt nach dem Alunit aus

Koloneia (Kütahya); es ist 9–12 Karat je

cantaro mehr wert als Alaun aus Foça.

Alaun aus Foça kommt nach der Sorte des guten Luminiera. Es ist

6–8 Karat der cantaro

mehr wert als Alaun aus Cotai, d.h. aus Ephesos.

Alaun aus Kütahya und Ephesus kommt nach dem Alaun aus Foça und

ist 4–6 Karat der cantaro

mehr wert als türkisches Alaun lupaio (aus Uluabat?).

Alaun lupaio (aus Uluabat?) kommt nach dem aus Kütahya und

Ephesus. Es ist 3–4 Karat je

cantaro mehr wert als Cysicus Alaun, Alaun

ghiaghillo und und Alaun corda.

Cysicus Alaun, Alaun ghiaghillo, Alaun corda

sind die schlechtesten Sorten, die aus Romania und der Türkei

entspringen.

Welche Preise und Sorten Wachs es in Romania und am Schwarzen Meer gibt, die in Pera und Konstantinopel münden; das bulgarische Wachs ist das beste, das aus diesen Orten (also Romania) stammt 4

[[gittata = gettata = geworfen]]Bulgarisches Wachs ist das beste Wachs aus Romania; es wird 11–12

Karat der cantaro höher bewertet

als das zu Päckchen gegossene (gittata) Wachs. Es ist gelber und stärker

gefärbt als das andere und es ist klar.

Wachs, das in Form oder zu Päckchen gegossen ist, kommt nach dem aus

Bulgarien; es ist 11–12 Karat der

cantaro mehr wert als das in Form gegossene aus

Asow und es ist klares Wachs.

In Form gegossenes Wachs aus Asow ist weder so gefärbt noch so klar wie

das zu Päckchen gegossene, außerdem enthält es Verunreinigungen,

d.h. Schmutz. Es kommt hinter dem zu Päckchen gegossenen.

Wiegegebühren für Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera

27

Für alles mit Gewicht, das nach cantara gewogen

wird, bezahlen der Verkäufer wie auch der Käufer für jedes Teil 3

Karat7

je zehn cantare.

44

Nur Genuesen sind in Pera frei, sie bezahlen keine Wiegegebühr.

Dagegen zahlen Venezianer und alle anderen die 3 Karat

je zehn cantara.

Für alles, was man nach Hundert Gewicht wiegt,

bezahlt jedes Teil 1 Karat pro Hundert.

Für Seide, Safran und alle feinsten Spezereien,

die man nach zehn Pfund2

oder nach Pfund verkauft, zahlt jedes Teil ½

Karat je zehn Pfund2.

Man ist nicht verpflichtet dem Waagemeister, einem anderen oder dem

Schreiber der Waage eine Gefälligkeit zu leisten; damit du jedoch deinen

Anspruch wahrst, solltest du ihm dennoch ein paar kleine Dinge – etwa

2–6 Karat – geben entsprechend dem Umfang, den du ihn wiegen lässt.

Wenn man ihm nichts gäbe, würde er das auch nicht verlangen.

Alle Dinge, die gewogen werden, muss der Verkäufer bringen und zum

Gewicht (also auf die Waage) legen; dann lässt der Käufer sie wegnehmen und zu

sich nach Hause bringen. Das kostet für die Träger, je nachdem wie weit

das Lager entfernt ist, etwa 8 bis 12 Karat je

Hundert cantaro. Allerdings hat

Alaun nicht so hohe Ausgaben, weil der Waagemeister zum Wiegen zur

Herberge bzw. zum Lager des Verkäufers geht. Daher kostet es den Verkäufer

nur 4 bis 6 Karat je Hundert

cantare, das Alaun auf die Waage zu legen.

Welche Steuern man bezahlt

Für Spezereien ist es die Aufgabe, sie in

Konstantinopel oder Pera zu versteuern. Die Steuer bezahlen der Verkäufer

und der Käufer zu gleichen Teilen je Stück, wie im Folgenden ausgeführt

wird:

- Pfeffer, Weihrauch, Ingwer, Mastix, Zimt, Zitwer, und alle anderen groben Spezereien, die man versteuert, 1 Karat pro hundert peso.

- Gewürznelken, weil sie mühsam (fatichevoli) auszusortieren sind, 1 Karat je zehn Pfund2.

- Kubeben-Pfeffer, Mazis, Muskatnuss, Rhabarber, hohes Zypergras, Kardamom, Gewürz-Lavendel, Legno Aloe und alle anderen feinen Spezereien, die man versteuert, 3 Karat je Hundert Pfund2.

28 Was man den Maklern von Waren in Konstantinopel und Pera bezahlt

Für alle Waren, die man wiegt oder auch nicht, bezahlt jedes Teile

4 Karat je 100 perperi.

Für Wollstoffe, egal woher sie sind, im

Großhandel, von jedem Teil 4 Karat je

100 perperi; wenn man jedoch nur 1 bis 3 Stücke

verkauft hat, bezahlt man 3 Karat pro Stück.

45

Drappi aus Gold, Kamelott, Drappi aus Seide, von jedem Teil

4 Karat je 100 perperi.

Für Getreide oder Weizen, von jedem Teil 4 Karat je

100 perperi.

Olivenöl, von jedem Teil 4 Karat pro 100

perperi; wenn man jedoch insgesamt nur ein oder zwei

Fass Olivenöl verkauft hat, bezahlt man nur 2 Karat

pro Fass von jedem Teil.

Griechische oder andere Weine, Verkauf in großen Mengen,

6 Karat je 100 perperi; wenn

du sie im Kleinen verkaufst, von 25 Fässer abwärts,

2 Karat pro Fass von jedem Teil.

Obgleich man, wie oben gesagt, lediglich 4 Karat pro

100 perperi zahlen muss, gibt man für die Waren

mehr, d.h. nicht weniger als 6, Karat je

100 perperi.

Für Geldwechsel, Wechselbriefe mit Liefergarantie oder auf Risiko, Gold,

Silber oder Geldbeträge (sommi), für das eine wie das andere,

2 Karat pro 100 perperi.

Für die Miete von Frachtraum, von jeder Einheit 6 Karat

pro 100 perperi2

von der Mietsumme des gecharterten Segelschiffs. Aber trotzdem werfen die

Makler einen Blick [[ auf das Ganze ]] und sie lehnen den Kapitän des

Schiffs bzw. den mietenden Kaufmann ab, je nachdem ob sie dem Makler das

eine oder andere Benötigte bereithalten: 10–25

perperi je Einheit, je nachdem welches Schiff es

ist. Wäre sie [[ die Rate ]] pro hundert, würde er [[ der Maklern ]] sie

nicht gewähren, wenn sie sich nicht auf die Miethöhe bezieht.

Wenn du in Pera auf einer Auktion einige Juwelen, wertvolle Steine, einen

Topf Gold oder Silber kaufst, musst du für jedes Teil 1

Karat pro perperi bezahlen,

was [für den Hundert perperi]

4 perperi und 4 Karat ergibt.

Gebühr für das Verpacken von Ballen (balla oder pondi) in Konstantinopel und Pera

Seide, gut verschnürt, für den Ballen 8 Karat.

29

Für alle Spezereien, die man zu Ballen gebunden

hat, wird ½ Karat je Ballen verlangt.